On September 3, we held the second session of our webinar series on “Disability Activism Under Pressure: Resistance and Resilience in Authoritarian Contexts“. Following on from our first conversation (you can find our reflections on our website), this instalment of La Yapa reflects on the session on Operating in an Age of Surveillance: Building Security Practices.

Moderated by Maryangel Garcia-Ramos (Women Enabled International), this session brought together Amir Rashidi (Miaan Group), Akwe Amosu (The Symposium on Strength and Solidarity for Human Rights), and Faith Obafemi (Fezzant) to share their experiences of navigating escalating surveillance, digital privacy, and the accessibility challenges of cybersecurity.

We are deeply grateful to our speakers and moderator for their time and generosity, and to everyone who joined us live. For those who missed it — or who want to revisit the discussion — the full recording is available with this link.

Key Takeaways

No one is exempt

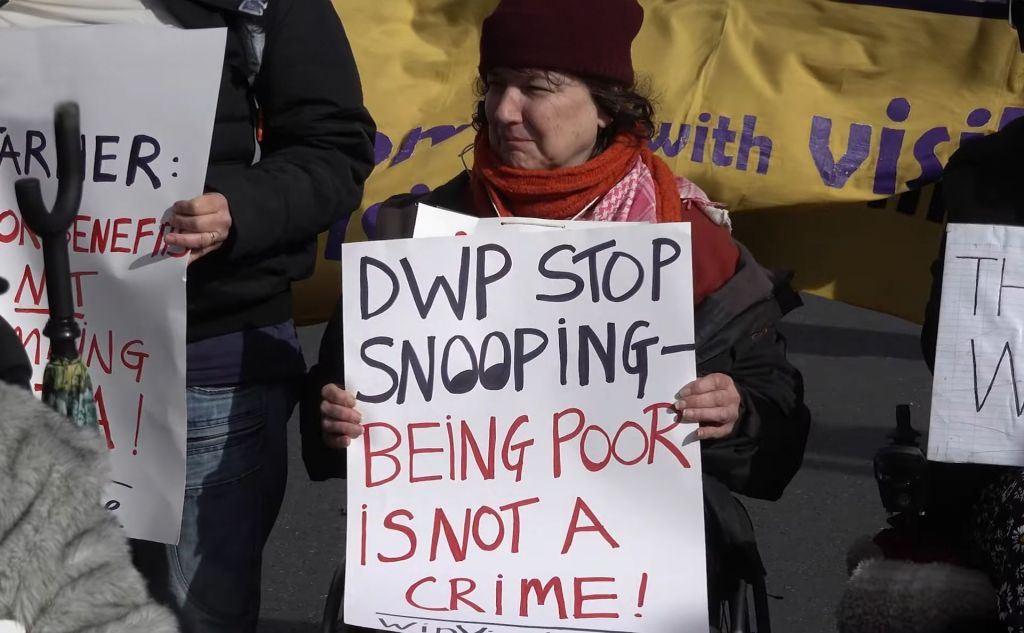

States are investing heavily in surveillance – from digital monitoring and data collection to community-level surveillance and criminalisation of dissent – to intimidate, silence, and isolate activists. The risks vary depending on activists’ focus and contexts. Our speakers cite examples such as internet shutdowns in Nigeria, spyware used against Serbian activists, surveillance of and cyber attacks on Iranian activists, and state aggression towards elderly or chronically ill people during pro-Palestine protests in the UK to highlight how everyone is at risk. Disability activists might believe they are not targets because their work isn’t considered “controversial”, but when they challenge the status quo, they are not exempt from these threats.

“Surveillance is not only about those being dangerous. It is a way to monitor anyone who organizes collectively or challenges state narratives.”

Maryangel Garcia-Ramos

Security as an act of solidarity

In a digitally connected world, surveillance not only targets individuals but also everyone they come in contact with. Even where individual security risks are low, movements face collective risk because of their inherently interconnected nature. We are only as secure as the least secure person in our network. For our movements to operate safely, “we have to keep each other safe”. For Akwe, whose work at the Symposium brought together human rights activists, this meant ensuring that all participants, irrespective of their personal risk level, adhered to a set of security practices.

“You should not think, ‘I’m not doing anything, I’m not a target.’ Even if you really are not a target, maybe you are actually an entry point to getting someone else who is in your network.”

Amir Rashidi

Some protection is better than none

Activists constantly make calculations about the trade-offs between convenience and security. Nothing can keep us completely safe from surveillance and privacy invasions in the face of the power and resources of states. Nevertheless, it is worth trying. In the absence of tools and technology that are fully accessible and fully secure, disabled activists have to find options that offer the highest level of both. In a rainstorm of surveillance, raincoats, umbrellas, or boots alone will not keep us dry. But each of them will provide some cover and that is better than getting drenched.

Changing behaviour takes practice

Our speakers acknowledged that security practices can feel cumbersome, inconvenient, and difficult to adopt. Amir stressed that while it is easy to say, “don’t use this tool, use the other”, changing habits is incredibly challenging. Faith added that this is particularly hard for disabled people because tools for protection are often not designed with accessibility in mind. Disabled activists, far from being exempt, are placed at greater risk.

“We have to go through a kind of mindset change in which we stop thinking about what the rules say and we start thinking about how we take care of each other, how others take care of us, and who we share the information with, and to what extent we’re all operating on the same principle.”

Akwe Amosu

Resources are critical

Keeping ourselves and each other safe requires resources. Funding is critical for organisations and activists to access necessary tools but also for the development of more accessible secure technologies. Knowledge is another critical resource. Effectively countering surveillance requires experts in technology, accessibility, and organising strategies to come together. Activists require training and information about risks and ways to mitigate them.

Accessibility and security need to be built in

Disability activists rely on technologies for accessibility, public services, support systems, and organising, but these same tools can be tracked and weaponized against them. At the same time, secure tools and even security training materials are often not accessible. As Faith pointed out “most secure tools are less popular, which often then translates to less accessibility”. This lack of accessibility stems from a systemic oversight: security is not designed with disabled people in mind from the start. Accessibility should be at the heart of our security practices.

“When there are security products being developed, they need to incorporate accessibility from even the idea stage. We shouldn’t wait for when things are already shipped out to begin to fix it or try to patch things up, but they should get design from the beginning to ensure that they’re accessible.”

Faith Obafemi

Tips, tools, and practices

Our speakers shared a range of practical resources from their own experiences. Faith provided some best practices for digital hygiene: using strong, unique passwords; keeping software updated; encrypting devices; and minimising shared information. From her work at the Symposium, Akwe described collective measures such as removing all devices with microphones (smart watches, phones, laptops) from meeting rooms and limiting the circulation of sensitive information. Amir talked about using Cubes OS and acquiring devices from trusted places.

Other concrete suggestions were using Signal for safer communication; using Pixel, Ghost, or Mastodon as alternatives to mainstream platforms; using Brave or Firefox as browsers to reduce tracking; and reaching out to organisations such as the Electronic Frontier Foundation, Citizen Lab, and Cyber Space Institute for information on digital security practices and tools.

Finally, Maryangel Garcia-Ramos reminded us that despite the dangers that tomorrow might bring, we have to hold on to hope, adding that “hope is a political decision that involves the tiny decisions of every day of how we’re making each other safe, how we’re thinking in solidarity, how we’re thinking of the impact of the way that we communicate”

What’s Next

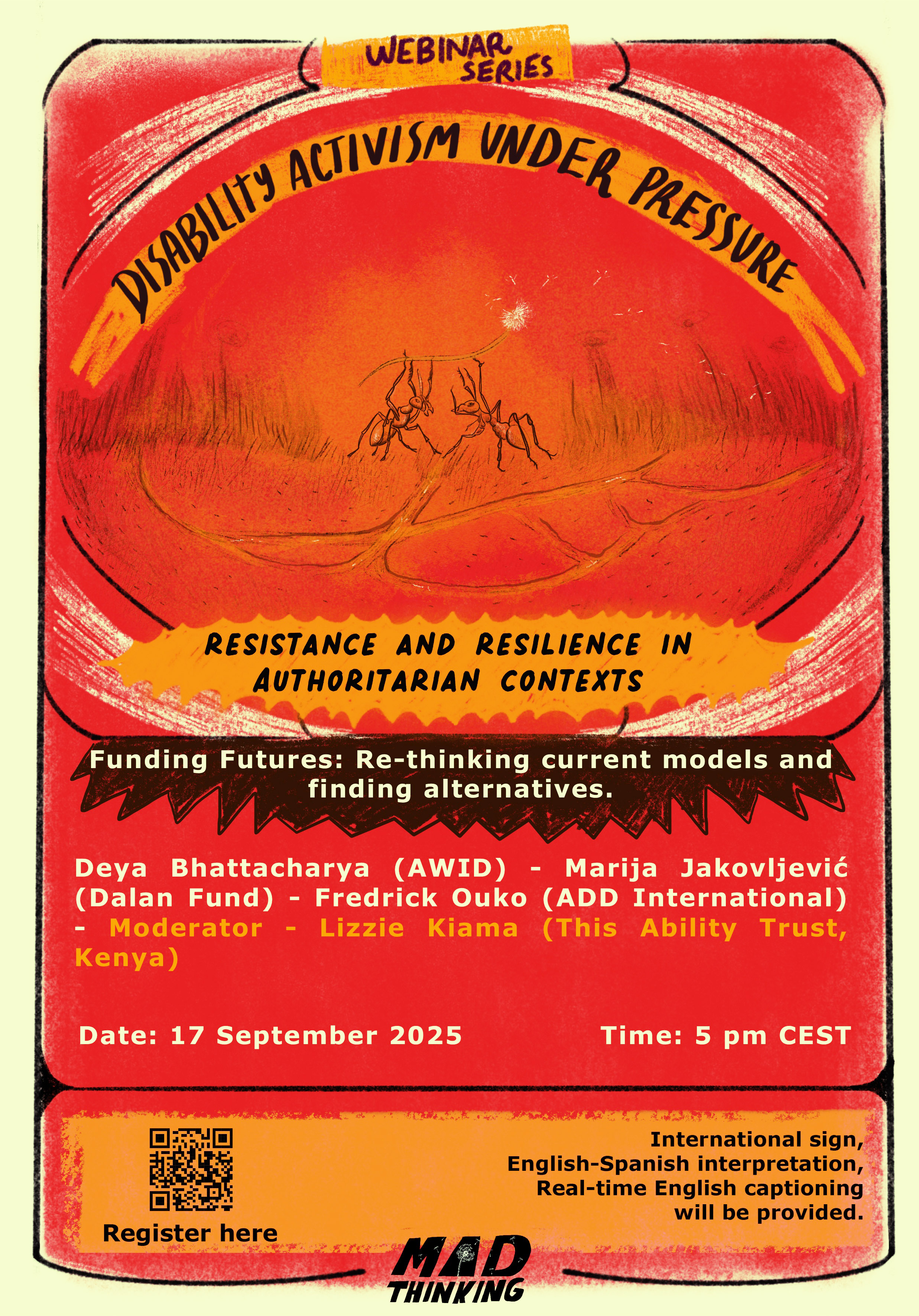

Our next session, Funding Futures: Re-thinking current models and finding alternatives, will take place on 17 September at 5 PM CEST. We hope you will join us to explore the limits and vulnerabilities of current funding models and the need to build sustainable ways to resource our movements. If you have not registered yet, you can register now.

In the meantime, explore the politics of funding at WHEELING – dare to apply?

Featured image: Disabled activists in the UK protest against the use of surveillance by the Department of Welfare and Pensions. Photo credit: Chronic Collaboration.