On October 1, 2025, Mad Thinking hosted the fourth session of its webinar series, “Disability Activism Under Pressure: Resistance and Resilience in Authoritarian Contexts.” Titled “Re-thinking How We Come Together: Building Diverse Structures of Organising,” the conversation explored how movements can resist fragmentation and rethink the very ways we organise, lead, and sustain collective power.

The session brought together Emilie Palamy Pradichit (Manushya Foundation, Thailand), Loan Tran (Rising Majority, U.S.), and Silvestre Barragán (ALCE, Colombia) — three organisers who each, in very different contexts, are building communities that defy hierarchy and centre lived experience. It was moderated by Alberto Vásquez Encalada (Mad Thinking).

We thank Emilie, Loan, and Silvestre for the depth and openness they contributed to this exchange, as well as everyone who joined us live from different parts of the world. You can watch the full recording via this link and revisit reflections from earlier sessions on our website.

Below are a few threads that stood out to us — a handful of reflections to carry forward as we continue thinking about what it means to organise differently.

Key Takeaways

Clarity about what we’re building

Loan noted that movements often unite around what we oppose — e.g., discrimination, police brutality, state violence — but struggle to stay connected around what we actually want. Without a shared vision for the future, our actions stay defensive, shaped by the agendas of those in power. Building coherence means defining that common direction: what a radical, bottom-up democracy looks like, what a regenerative economy requires, and how we align our struggles around the future we’re moving toward.

We organise for the long term

Amid growing repression, it’s tempting to focus only on immediate survival. Yet building power that lasts means thinking beyond the next crisis — tending to relationships, knowledge, and structures that can outlive individual moments or leaders. As the speakers reminded us, authoritarianism thrives on fragmentation and fatigue; our task is to build movements resilient enough to endure both. It also calls for humility to recognise that many before us have faced similar battles, and that our strength lies in listening, learning, and carrying forward their wisdom.

“At any given moment, we can actually do at least three things. That might be connecting with another person, taking an action with a group of people, or planning for the future. We have to resist, in this moment, the idea that we are completely powerless. We’re not. We can do things. We just have to take a moment to remember what those things are.”

LOAN TRAN

Solidarity doesn’t need to be fixed

Emilie reflected that movements don’t have to be rigid or neatly defined to hold power. The Milk Tea Alliance — a leaderless, decentralised online network linking pro-democracy movements across Asia — illustrates how solidarity can emerge organically, appearing when needed, pausing when it’s less so, and reshaping itself in new forms. Its strength lay in creativity and flexibility, not structure. In an era when institutions and donors often demand structure, permanence, and visibility, these fluid ecosystems of resistance demonstrate that what matters most is connection and common purpose, not form.

Disagreement can strengthen us

Unity doesn’t mean everyone agrees — it means we know how to move forward together despite our disagreements. Within large coalitions, insisting on complete consensus can impede collective action, while disagreement, when held with care and discipline, can sharpen strategy and deepen trust. The goal is not to avoid conflict but to practise it in ways that build alignment rather than fracture it; learning when to step forward, when to step back, and when to let others try something new.

Confronting hierarchies within our own spaces

Even within movements for justice, power is never neutral. When leadership and resources concentrate among a few privileged voices, our organising reproduces the colonial, class, gender, and ableist hierarchies we seek to dismantle. Confronting these internal dynamics requires honesty about who holds power and whose voices shape priorities, the self-awareness to shift leadership toward those closest to the struggle, and a commitment to redistributing resources within our movements.

“If we just bring Indigenous women, feminist voices, people with disabilities in the room as a way of representation, how do we know that’s not just tokenism? If those people are in the room but the outcome is exactly the same as if they were not in the room, then that is tokenism.”

Emilie Palamy Pradichit

Leadership is a shared practice

The conversation reminded us that strong movements are not built around individual heroes but around collective leadership. Leadership takes shape through relationships — in how people support one another, share responsibility, and make decisions together. In contexts of repression, decentralised leadership is also a matter of safety: when power is shared, movements become harder to target and more resilient.

Collective care keeps us alive

The most effective forms of solidarity rarely come from institutional mechanisms, but from communities that organise together and care for one another in practical, political ways. Building our own networks of support — from emergency safety nets to peer-to-peer systems — is how movements prepare for crises without waiting for donor approval or external permission. Collective care is not just a gesture; it’s a form of resistance that helps us withstand exhaustion and repression.

Beyond accessibility

The discussion also invited reflection on why disability movements so often remain apart from broader struggles. As Silvestre noted, accessibility continues to be a real barrier — in physical environments, communication, and spaces — but separation also stems from a lack of broader perspective, segmented strategies, and the ways we organise ourselves. Connecting across movements requires more than technical fixes: it demands mutual learning and the courage to stay in dialogue despite differences. And building that trust takes time and effort. Authoritarianism thrives on fragmentation; solidarity depends on our capacity to bridge it.

“We seek to understand disability not in an isolated place, but in how it weaves through other matrices of oppression. We cannot think of mad people in one place and trans people in another, when in reality, from an intersectional perspective, it is something that runs through all of us, as people called to be normalised. So how do we generate that broader perspective that can call for solidarity among different movements?”

Silvestre Barragán

What’s Next

Across the first four sessions, we have explored what it takes to keep organising under growing constraints. We began by examining how today’s authoritarianism operates — not through a single ideology, but through a shared toolkit. We then discussed what it means to survive in an age of surveillance, to rethink how we resource our work without reproducing dependency, and to build structures of organising that are diverse, grounded, and collectively led.

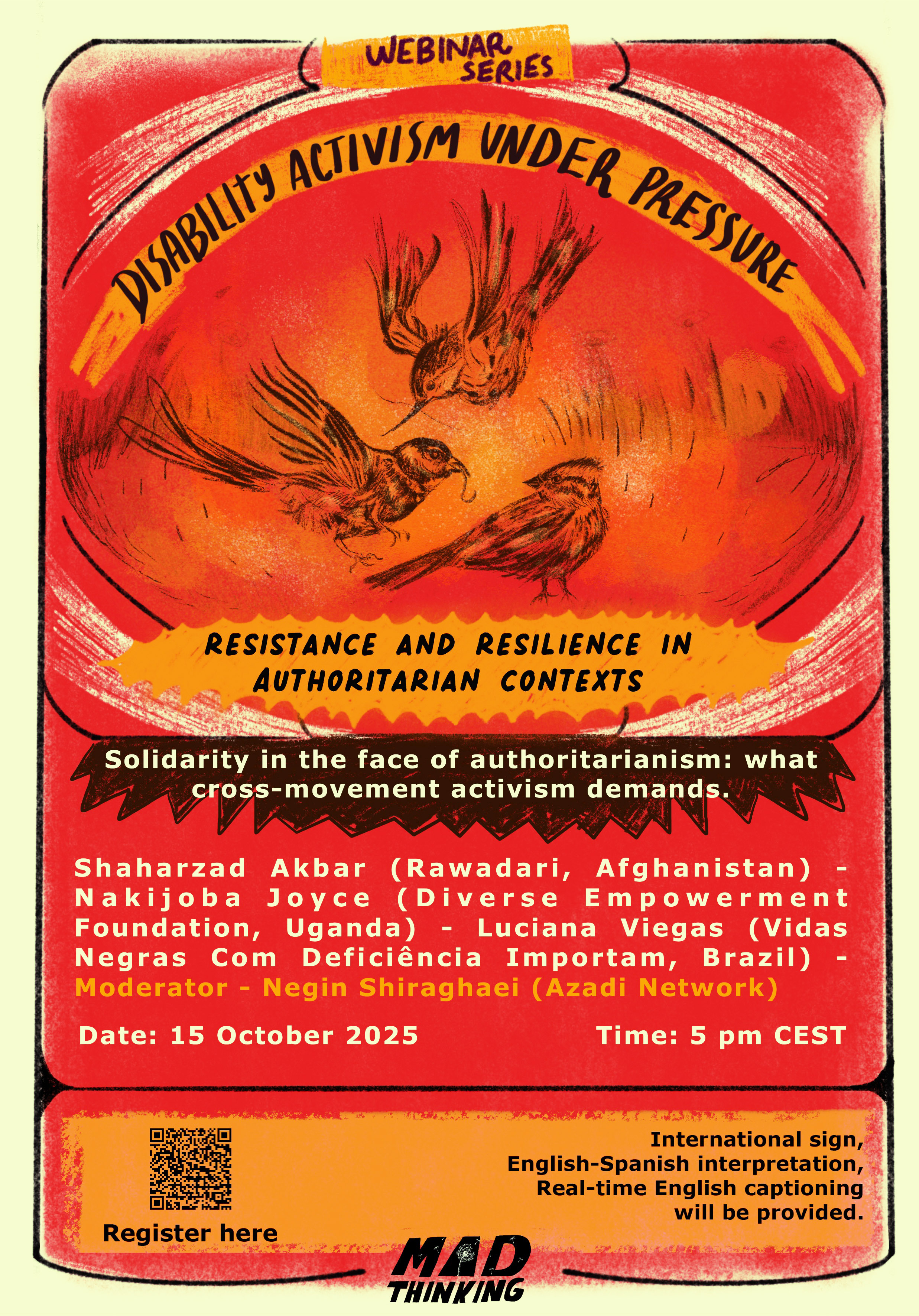

Next, on 15 October 2025, in Session Five, “Solidarity in the Face of Authoritarianism: What Cross-Movement Activism Demands”, we will bring these themes together to explore what solidarity looks like in practice: how we protect one another and build alliances that cross movements, identities, and borders.

If you have not registered yet, you can register now.

Featured image: A screenshot from a video documenting the 2025 Nepalese protests